Caveat emptor, quia ignorare non debuit quod jus alienum emit.

(“Let a purchaser beware, for he ought not to be ignorant

of the nature of the property which he is buying from another party.”)

Prologue

Let’s start with two questions.

Question #1: Should you have the right to know when you’re being advertised to?

Question #2: Should you have the right to know who is advertising to you?

Both questions lie, so to speak, at the heart of stealth marketing, which takes the form of product placement, custom content, native advertising, brand journalism, your euphemism goes here. They are all, in the end, ads in sheep’s clothing.

The answer to Question #1 has traditionally been yes, with audiences expecting clear distinctions between advertising and editorial content.

But as we know, tradition is generally out of style nowadays. So myriad media publications have lured myriad marketers (and their myriad marketing dollars) with the promise of ads tricked out as something other than advertising.

The deception is the point for stealth marketers: The less apparent the selling is, the less it triggers the average consumer’s natural resistance to being sold. Rule of thumb: the more opaque the sales pitch, the better.

The interests of reputable publishers, by contrast, run counter to those of stealth marketers: The more that readers/listeners/viewers find themselves duped into mistaking advertising for editorial content, the more a publication’s integrity and credibility could be eroded.

That tension was neatly captured by legendary media critic A.J. Liebling, who wrote in the 1960s, “The function of the press in society is to inform, but its role in society is to make money.”

In the 21st century, stealth marketing has come to represent a major source of that money. In 2019, U.S. product placement rang up over $11 billion in spending, while native advertising expenditures in the U.S. approached $53 billion in 2020.

That’s real money for fake content.

As for Question #2, it’s instructive to examine the work of lawyer/lobbyist Rick Berman, who – as CBS’s 60 Minutes reported in 2007 – revels in the nickname “Dr. Evil.”

Berman is in the business of establishing fog-machine front groups to promote corporate interests ranging from the fast food industry to soft drink manufacturers to Big Tobacco to any corporation fighting minimum-wage increases.

Here’s a partial portfolio of Rick Berman’s Potemkin Non-Profits.

The Center for Media and Democracy’s Source Watch characterized Berman’s grift this way.

Berman & Co., a Washington, DC public affairs firm owned by lobbyist Rick Berman, represents the tobacco industry as well as hotels, beer distributors, taverns, and restaurant chains. Berman & Co. has lobbied for companies such as Cracker Barrel, Hooters, International House of Pancakes, Olive Garden, Outback Steakhouse, Red Lobster, Steak & Ale, TGI Friday’s, Uno’s Restaurants, and Wendy’s.

Berman & Co. operates a network of dozens of front groups, attack-dog web sites, and alleged think tanks that work to counteract minimum wage campaigns, keep wages low for restaurant workers, and to block legislation on food safety, secondhand cigarette smoke, and drunk driving and more.

In 2013-14, Berman and his Employment Policy Institute “think tank,” have led a national fight against campaigns to raise the minimum wage and to provide paid sick leave for workers with renewed attacks on proponents (including the Center for Media and Democracy, publisher of Sourcewatch), misleading reports, op-eds, TV and radio ads and more.

Source Watch has tons more dirt on Berman if you’re so inclined. You can also review some of Berman’s handiwork at my blogs Sneak Adtack, Campaign Outsider, and It’s Good to Live in a Two-Daily Town.

Also instructive: Berman’s 2009 tango with MSNBC’s Rachel Maddow here and here.

But this has to be the quintessential Rick Berman story.

The roll call of Berman’s front groups featured above came from the website BermanExposed.org, which was dedicated to tracking the corporate gunsel’s endless smoke-screen campaigns.

But somehow, somewhere along the line, Berman co-opted/acquired the BermanExposed URL so that when you go there now, you get this.

To recap: Changing the Debate means not only that Berman is reframing public-policy issues to serve the corporate interests of his clients, but also that he’s turned BermanExposed into BermanSuperimposed.

That’s not even evil. That’s just brilliant.

Then again, let’s step back and play devil’s advocate for a moment.

Take the issue of what Berman’s ads call the Food Police, those government agencies and officials who want to regulate the consumption of trans fats, sugar, salt – anything the public health community deems potentially harmful to the well-being of the average American.

Question #3: Is the role of government regulation regarding individual choices a legitimate issue for debate?

If so, Question #4: How does that debate happen?

Let’s say McDonald’s runs a nationwide advertising campaign that opposes federal restrictions on trans fats. Would the fast-food chain’s argument be taken seriously by the American public, or would it be dismissed as a naked attempt to promote McDonald’s financial interests?

If the issue of government regulation of trans fats is indeed a legitimate subject of debate, wouldn’t the American public be better served if those regulations were opposed by what seemed to be a neutral party – even if, in reality, it wasn’t neutral?

In other words, does Rick Berman’s duplicity actually foster a more worthwhile public debate?

We know: It hurts to say that maybe it does.

But maybe it does.

CODA: The redoubtable Charles Merzbacher of Boston University adds this:

The story of Rick Berman is even darker than you suggest–and considerably more depressing. Berman’s son was the noted rock musician David Berman, the guiding light behind the cult band Silver Jews. David was deeply ashamed of his father’s hateful shysterism, to the point where he eventually withdrew from making music in order to devote himself full-time to debunking and exposing his father’s work. I’m pretty sure David was a guiding force behind the “Berman Exposed” website. In any case, David’s despair over his father’s activities, combined with other emotional and financial problems, led him to commit suicide in 2019. It is therefore entirely possible that Rick Berman’s coopting of the “Berman Exposed” site was a direct or indirect windfall from his son’s untimely death. How do you like them apples?

Wow. Just wow.

The Sneak in Review

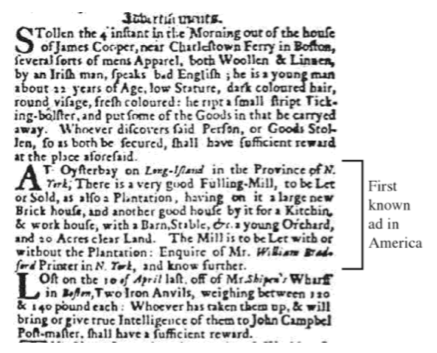

There has been stealth marketing in American media since the very beginning of American media.

As Juliann Sivulka noted in her book Soap, Sex, and Cigarettes: A Cultural History of American Advertising, the first known ad in America was embedded in the 1704 Boston News-Letter.

It’s also the first example of native advertising – an ad fashioned to look like the editorial content surrounding it.

Sivulka futher notes that the first great American adman was Benjamin Franklin, who founded the Pennsylvania Gazette in 1728. Franklin “created the first known illustrations to appear in an American newspaper” and pioneered the placement of ads on Page One.

Beyond that, in 1741 “Franklin’s General Magazine was the first known American magazine to carry an advertisement – for a ferry service across the Potomac River from Annapolis to Williamsburg.”

Roughly one hundred years later, another illustrious figure in American history also engaged in some breakthrough marketing.

In the run-up to his 1860 presidential campaign, Abraham Lincoln secretly purchased the Illinois Staats-Anzeiger, an influential German-language newspaper in Springfield, Illinois.

The paper subsequently, and not surprisingly, published editorials in support of – wait for it – Slightly Less Than Honest Abe.

Let’s charitably call that an early example of brand journalism.

• • • • • • •

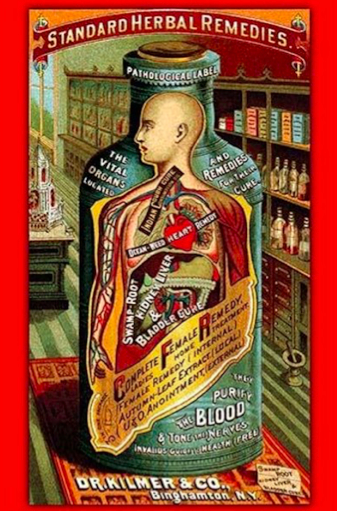

In 19th century America, patent medicines were soda pop for the sickly.

Patent medicines were also parity products – that is, largely identical – which led them to rely on branding to distinguish one from another. In his book 20 Ads That Shook the World, James B. Twitchell detailed the patent medicine bakeoff.

[Since] the package was almost always a glass bottle, the container really wasn’t important. It was what you put on the label and in the advertising that really moved the stuff off the shelves.

“Bells and whistles “ barely describes the outrageously creative copy and pupil-dilating art of patent-medicine advertising. Some of the most sublime commercial artwork ever produced was lavished on picturing the restorative results of these pick-me-ups.

In the end, though, the problem wasn’t that patent medicine ads were too elaborate. The problem was there were too many. By one estimate, at mid-century patent medicine ads accounted for more than half of the advertising lineage in many papers.

Beyond that, about one-third of U.S. publishers’ revenue came from ads like this one.

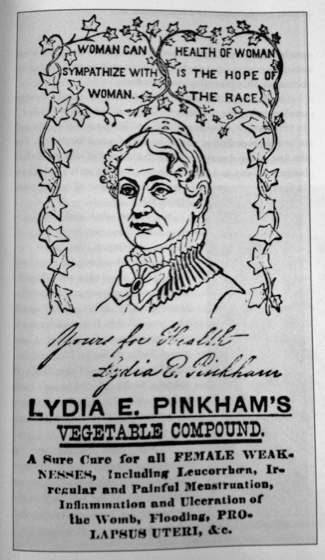

Patent medicine pioneer Lydia E. Pinkham, however, had a different approach for her branding. The pride of Lynn, Massachusetts went clean and simple and sympathetic.

Lydia Pinkham became nationally known for her Vegetable Compound tonic thanks to some truly innovative marketing approaches, not to mention the tonic’s 18% alcohol content.

Starting in 1875, Pinkham essentially invented relationship marketing, pitching her Vegetable Compound as the cure for female complaints ranging from cramps to hot flashes to sleeplessness to depression.

“Woman can sympathize with woman” was her slogan, and Lydia (or someone employing her signature) would answer each letter she received from female consumers.

But as Twitchell notes in 20 Ads That Shook the World, the real marketing maven was not Lydia, but her son Dan.

Although his name is rarely acknowledged in the pantheon of advertising genuises, it should be. Here’s some of what he did. Once he paid young women to write on small cards, ‘Try Lydia E. Pinkham’s Vegetable Compound and I know it will cure you, it’s the best thing for Uterine complaints there is. From your cousin, Mary – P.S. You can get it at . . . ‘ He then scattered the cards around cemetaries on the days before Decoration Day.

Exploiting the families of wartime casualties was, of course, entirely reprehensible.

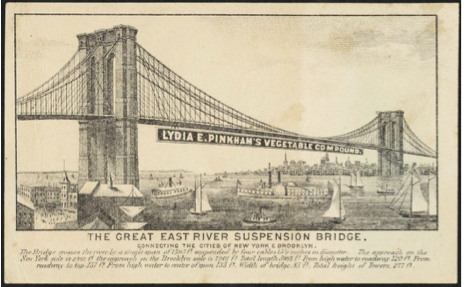

Consequently, it’s not at all surprising that Dan Pinkham also managed to sell the Brooklyn Bridge to unsuspecting women.

That banner [checks notes] never got anywhere near The Great Bridge. Chalk it up to an early example of custom content.

• • • • • • •

There’s plenty of blame to go around for the emergence of product placement, as Alex Walton noted in The Evolution of Product Placement in Film.

Although the term ‘product placement’ seemed to have been coined in the 1980s, the practice actually dates back to before the beginning of motion pictures. There are clear examples of product placement in stage performances and art that predate motion pictures.

In Edouard Manet’s painting Un Bar aux Folies Bergère, for example, there is clear portrayal of Bass beer.

Here’s Manet’s Bass relief.

More from Walton:

Charles Dickens’s The Pickwick Papers also could be considered product placement as the name Pickwick comes from a carriage line that appears in the novel.

On the stage, Sarah Bernhardt wore La Diaphane powder and also served as a spokesperson appearing on the brand’s posters.

According to the website William Friese-Greene & Me – created by Peter Domankiewicz, a director and writer for feature films and television – Thomas Edison likely made the first ever video commercial in 1897. (Friese-Greene was a British inventor/photographer and a pioneer in the development of motion pictures.)

Campaign, the leading magazine for the advertising industry, crowns Edison as The First (as do many others) for his groundbreaking foray into the world of sell sell sell for… Admiral Cigarettes!

In it, guys smoke cigarettes – John Bull, Uncle Sam, some other bloke and yet another who, in an early homage to Justin Trudeau, is got up as a Native American – a woman bursts out of box, dressed as an admiral in tights, smokes fags (if you’re from the US you may need to research that phrase), chucks fags around, fags rain down, they unfurl a banner declaring WE ALL SMOKE, they all smoke, everyone’s happy. Brilliant.

That spot is here.

Actually, a year earlier France’s Lumiere Bros., Edison’s main rivals at the time, had engaged in a bromance with Lever Bros. to promote their Sunlight soap brand.

From The Hidden History of Product Placement:

In May 1896 . . . [Cinematograph] operator Alexandre Promio shot a film of two women hand-washing tubs of laundry. Placed prominently in front of the tubs were two cases of Lever Brothers soap, one with the French branding “Sunlight Savon,” the other with the German “Sunlight Seife.”

That spot is here.

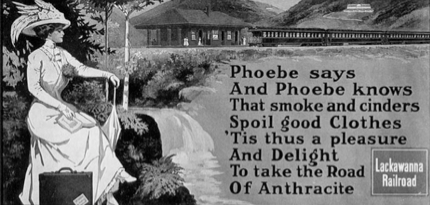

In 1903, though, Edison had an even brighter idea.

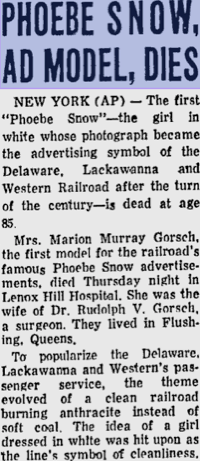

He wanted to make a silent film called The Great Train Robbery, but to do that, of course, he needed a train. At the time, one of the best known railroad lines was the Delaware, Lackawanna & Western, which had recently launched a high-profile ad campaign featuring the character Phoebe Snow.

According to this New-York Historical Society piece, “[to] capitalize on Phoebe’s celebrity, the Lackawanna Railroad hired the 23-year-old New Haven, CT, actress Marian E. Arnold-Murray [stage name: Marie Murray] to act as Phoebe and serve as a public ambassador for the train line.”

Edison’s totally brighter idea? He cast Murray as a Dance-Hall Dancer in the film, and got to use the Lackawanna’s trains. Both of Murray’s gigs were mentioned in this obituary from the Gettysburg Times of August 7, 1967.

For his part, Edison would go on to milk product placement like Elsie.

According to The Hidden History of Product Placement, “[Edison] turned product placement into an ongoing business that provided twin benefits of reducing out-of-pocket production expenses while providing promotional services for customers of his industrial businesses – as in, travel films subsidized by transportation companies.”

Nice work if you can get it . . .

• • • • • • •

At the turn of the century there was also a turn of the media – from a print-dominated universe to an electronic era that would project a very different image of the world.

As media theorist Neil Postman noted in his landmark 1984 book Amusing Ourselves to Death, in a culture dominated by print, public discourse tends to be characterized by a coherent, orderly arrangement of facts and ideas.

But the electronic era – starting with the telegraph in the mid-19th century and accelerating thereafter into film, radio, and television – created a world of instantaneous and simultaneous information that, Postman said, was essentially context-free and divorced from any social or political significance.

If the typographic era led people to perceive the world as linear, uniform, sequential, coherent – like the printed page! – the electronic era led people to perceive the world as random, centerless, and chaotic.

As Media Theorist 1.0 Marshall McLuhan (Postman was 2.0) wrote in Understanding Media, the electronic era ended sequence by making things instant. “Instead of asking which came first, the chicken or the egg, it suddenly seemed that a chicken was an egg’s idea for getting more eggs.”

Welcome to the 20th century!

This Program Brought To You By . . .

“The act of a person who steals your screen is no different than the act of a person who steals your watch.”

– Movie Exhibitor Newsletter, 1925

In the early decades of the 20th century, product placement was the commercial soundtrack of the American film industry.

As Alex Walton of Elon University writes, “Will Hays, the head of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America (MPPDA), said at the time ‘[The motion picture] is the greatest agency for promoting the sales of American-made products throughout the world.’”

Many early product placements were cross promotions in which the films would feature products and the product manufacturers would create advertisements promoting the film.

The New York Times noted the trend of brands getting their products in films in a 1929 article. According to the Times, “Automobile manufacturers graciously offer the free use of high-priced cars to studios. Expensive furnishings for a set are willingly supplied by the makers, and even donated as permanent studio property.”

Perhaps reacting to that system of cinematic gift-with-purchase, then-Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover decided to lay down the law about the prospect of advertising on the public airwaves in a February, 1922 speech concerning the nascent radio medium.

This material must be limited to news, to education, and to entertainment and the communication of such commercial matters as are of importance to large groups of the community . . .

It is inconceivable that we should allow so great a possibility for service to be drowned in advertising chatter.

(To be clear graf goes here)

To be clear, that was not actually a law, but more what you’d call a guideline.

Sure enough, six months later the first radio commercial ran on WEAF in New York – a fifteen-minute spot for apartment homes in Hawthorne Court, at the time a new development in Jackson Heights, Queens. The Queensboro Corporation paid $50 for the airtime.

Hoover was not alone in his opposition to the commercialization of radio. Also in 1922, the trade publication Printer’s Ink editorialized that “[the] family circle is not a public place, and advertising has no business intruding there unless it is invited.”

In fact, early radio broadcasters were so concerned about propriety that announcers were required to wear dinner jackets during evening broadcasts as a sign of respect for the audience, despite the people at home not being able to see them.

Even as the Queensboro Corporation hoovered up three more commercials on WEAF shortly after its first spot, there was no stampede of advertisers to radio in its early years.

According to Juliann Sivulka in Soap, Sex, and Cigarettes, only 20% of radio programs had sponsors by 1927.

What eventually lured advertisers was the development of regular weekly programs such as musical variety shows sponsored by consumer brands and produced by their ad agencies.

Even then, though, advertising was slow-walked into radio, as Sivulka notes.

Most stations permitted only a single mention of the sponsor and the product name during their programs. The agencies, however, artfully circumvented the limitation and managed to insert the sponsor’s name at various intervals. For example, the writer for the Gold Dust washing powder program managed to refer to the sponsor’s name six times in one opening spot.

The radio medium itself also expanded slowly: licensed stations grew from 30 in 1920 to 576 in 1923. By 1929, only 40% of American families owned a radio.

The advertising at that time sold a company’s name rather than a specific product. Sponsors couldn’t even mention prices until 1932.

As James B. Twitchell notes in 20 Ads That Shook the World, “it took about twenty years for radio to be colonized by commercial interests.”

It took far less time, however, for radio to be colonized by one commercial character.

• • • • • • •

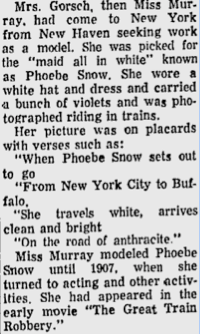

Betty Crocker was the daughter Lydia Pinkham never had.

Betty emerged much the same way Lydia did – from letters sent by women seeking advice on how to cope with their everyday problems.

As Susan Marks chronicles in her definitive biography, Finding Betty Crocker: The Secret Life of America’s First Lady of Food, it all started in 1921 when the Washburn Crosby Co. of Minneapolis, which produced Gold Medal flour, held a pin-cushion-giveaway contest that drew 30,000 responses, many of which included questions about baking and recipes.

The company’s ad manager, Samuel Gale, initially had male staffers get answers from the female Gold Medal Home Service staff, but eventually wanted a woman to answer customers.

So he invented Betty Crocker – last name from a retired company director, first name because it sounded cheery.

The 1920s found young women in a challenging position. Many moved from rural to urban areas seeking new opportunities while distancing themselves from older relatives who would normally help them cope with married life and motherhood.

Absent their own mothers and grandmothers, they turned to women’s magazines and marketers, as Marks details.

Early-twentieth-century admakers capitalized on the popularity of the late-nineteenth-century domestic science movement and the turn-of-the-century home economics movement by elevating influential females, such as the renowned home economist Fannie Farmer, to the position of trusted national experts. The push to feminize product presentation made sense, considering women controlled 80 to 85 percent of consumer spending . . .

Upon her debut in 1921, Betty Crocker added her voice to a chorus of female domestic experts – Mary Dale Anthony for S.O.S. scouring pads; Mary Hale Martin for Libby’s [baby food]; and Aunt Sammy (Uncle Sam’s wife) for the U.S. Bureau of Home Economics. These and all “personal advisers” were presented as actual women, but only a few were. The distinction seemed of little consequence.

That distinction totally evaporated with Betty. Starting with her 1924 radio debut, Betty Crocker became far more real than any of her sisters in marketing.

• • • • • • •

This hour – 10:45 every morning – is yours and I am here to be of service to you.

Betty debuted on Minneapolis-St. Paul station WCCO (which Washburn Crosby had purchased in 1924) with two programs: The Betty Crocker Service Program and The Betty Crocker Cooking School of the Air.

She was “of service” to her listeners primarily about food, dishing out do’s and don’ts such as this slightly unsavory one: “If you load a man’s stomach with soggy boiled cabbage, greasy fried potatoes, can you wonder that he wants to start a fight, or go out and commit a crime? We should be grateful that he does nothing worse than display a lot of temper.”

That would be cold comfort to an abused housewife, but why get technical about it.

Betty’s counsel also ran the gamut from “female” concerns to housekeeping, time management, husbands, friends, and relatives.

A year after Betty’s Minneapolis radio debut, Washburn Crosby expanded its broadcasts to twelve cities across the U.S. – New York to Philadelphia to Cleveland to Chicago to St. Louis to Los Angeles.

And so there were a dozen Bettys, all of them reading the same scripts distributed from the company’s “mother kitchen.”

Too many Bettys, as it turned out, threatened to spoil the selling. So in 1927 the dozen Bettys merged into one: Marjorie Child Husted – newly promoted, Marks writes, from a Gold Medal Flour home economist to director of the Home Service Department. She would personify Betty for the next 20 years.

‘You can do it and I can help you’ was Betty’s resolute validation. Betty’s message – that women at home were exactly where they were needed most – was hardly novel, but her delivery was . . .

Betty Crocker won far more notice for her innovative recipes than for her theatrical flair. Yet the performance aspect of her radio shows is often overlooked. Like the most sought-after celebrity, Betty was simultaneously accessible and aloof, appearing to have it all, do it all, and be slightly above it all.

As Marks concludes, “The commercial motive behind each friendly piece of advice was easy to overlook in the pleasure of Betty’s company.”

• • • • • • •

Betty Crocker didn’t start out to be a stealth marketer; she slowly morphed into one, caterpillar-like.

From the beginning, as Susan Marks writes, Betty was framed as a trusted adviser. “Betty undoubtedly offered realistic and timely advise to women in the 1920s, given their limited options for work outside homemaker, wife and mother.”

But Marks also notes that Washburn Crosby took it one step further, presenting Betty as a real person.

From her very first radio broadcast, the truth was carefully guarded, especially by the actresses who played her. The only admission made on air was that Betty Crocker did not do the recipe testing alone, but rather in the company of her growing Home Service staff. It’s reasonable to speculate that most listeners genuinely believed in Betty Crocker.

Marks adds that Washburn Crosby did not “deliberately set out to deceive customers. Yet [the company] did not officially set the record straight for many years.”

Then again, “set the record straight” is accurate the way Velveeta is cheese – marginally true but not substantially.

As Marks reports, “[I]n 1945, Fortune magazine called Betty Crocker the second most popular woman in America, trailing behind only Eleanor Roosevelt.”

As fond as Fortune seemed to be of Betty, in the glowing profile the publication has no qualms about delving into her quasi-secrets. The magazine publicly “outed” Betty, calling her “purely imaginary” and divulged her net worth: “$1 on the General Mills accounting books.”

But that hardly meant Betty was cooked.

Betty Crocker maintained her popularity – and her marketing profile – for another five decades.

Nowadays Betty Crocker no longer has a face. She survives primarily as a website and a Facebook page. Although Betty’s consumer profile has declined, her cultural cachet has not.

Two recent examples:

This excerpt from Jess McHugh’s book Americanon, which appeared in Literary Hub under the headline How a Single Cookbook Shaped What It Meant to Be an “American Woman.”

Betty Crocker’s Picture Cook Book is the best-selling cookbook in American history, with approximately 75 million copies sold since 1950. Not only did it guide generations of women in the kitchen; it was a cultural force, functioning as a blueprint for what it meant to be a good wife and mother. Cookbooks are one of those banal texts that we might ignore or dismiss, but this one, like so many others‚ tells a story about U.S food and everything that is wrapped up in it: family, power, class, culture, ethnicity, gender—and what it means to be American.

Beyond that, Betty was also apparently a Cold Warrior, as depicted in Tamar Adler’s New York Times piece Betty Crocker’s Absurd, Gorgeous Atomic Age Creations, which celebrates the 1971 Betty Crocker Recipe Card Library – the Rosetta Stone of 20th century Middle America.

As Adler writes:

Rachel Laudan, a food historian and author of the 2013 book ‘‘Cuisine and Empire,’’ thinks that behind the Betty Crocker recipe box lurks the Cold War — that these glossy cards were another theater for the standoff between socialism and capitalism, a version of the message that ‘‘abundance was something to be celebrated.’’ Surely the lush profusions on each card stand in diametric opposition to the Soviet aesthetic of the day, with its homemade loaves of dark bread, its communes and caps and kvass.

Stick that in your shoe, Nikita Khrushchev.

• • • • • • •

In 1950, 9% of American households had a television set. Remarkably, by the end of the decade it was close to 90%. As it grew into a mass medium, television initially adopted the same approach to advertising as radio had: programs sponsored by consumer brands and produced by their ad agencies.

That approach, however, soon proved too costly for the sponsors, so spot commercials became the standard format for advertisers. TV broadcasters – extensions of the NBC, CBS, and ABC radio networks – took over producing the programs, which gave them more control, and more quality control, over their content.

At the same time, Americans evolved from citizens to consumers. During World War II it was considered patriotic to Use it up. Wear it out. Make it do. Or do without.

After the war, it was patriotic to keep up with the Joneses.

Throughout the 1950s, television – and television ads – in many ways taught Americans how to be consumers again after decades of 1) Depression-era deprivation, and 2) wartime rationing.

Beyond the commercials touting branded products, the programs themselves – from I Love Lucy to The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet to Leave It to Beaver – provided viewers with a picture of what they should aspire to acquire for themselves.

Then again, not every analyst would use the word “taught” to describe advertising’s influence at that time. The 1950s also saw the rise of motivational research in the ad industry, a movement that was highlighted – and denounced – in Vance Packard’s 1957 exposé, The Hidden Persuaders.

In the introduction to the 50th anniversary edition of Packard’s best seller, Mark Crispin Miller writes that from the 1920s to the mid-‘50s, “advertising had been generally conceived as a coercive din, drummed up everywhere to browbeat, addle and/or mesmerize the masses into squandering their hard-earned wages on a lot of glittering junk.”

But Packard changed that with his focus on the motivational researchers (Marshall McLuhan called them “Madison Avenue frog-men of the mind”) who, Packard asserted, were turning advertising manipulation into psychological warfare.

Large-scale efforts are being made, often with impressive success, to channel our unthinking habits, our purchasing decisions, and our thought processes by the use of insights gleaned from psychiatry and the social sciences. Typically these efforts take place beneath our level of awareness, so that the appeals which move us are often, in a sense, “hidden.”

Upon the book’s publication, the New Yorker called Packard’s exposé a “frightening report on how manufacturers, fund-raisers, and politicians are attempting to turn the American mind into a kind of catatonic dough that will buy, give, or vote at their command.”

Funny, I had no idea that dough – catatonic or otherwise – could buy, give, or vote.

Then again, I’m no Vance Packard.

Miller added that “The Hidden Persuaders inadvertently gave rise to a persistent myth about the prevalence of ‘subliminal’ appeals, or ‘implants’: words or images that make us hungry, thirsty, scared or (mostly) horny, even though the naked eye cannot detect them.”

The truth is, motivational research – when it was used, which was intermittently – proved effective enough that subliminal messages would have been superfluous. And so they were largely non-existent.

The advertising machine, as it turned out, ran just fine on regular unleaded.

For the next four decades, the advertising landscape remained largely the same. To be sure, the number of media outlets grew dramatically, while ad clutter grew exponentially.

But advertising and editorial content (or ads and programming) were – like children and matches or Tom Wolfe and a spaghetti dinner – diligently kept apart, separated by what was called the Chinese Wall.

When the 21st century arrived, though, the Chinese Wall turned into the Berlin Wall – torn down and sold off brick by brick.

This Product Brought To You By . . .

For most of the 20th century, product placement represented the major form of stealth marketing. By the early 21st century, however, it was only one of a variety of ads in sheep’s clothing that ranged from custom content to brand journalism to native advertising and beyond.

By 2010 TV programs were absolutely larded with product placements – or, for those willing to pony up bigger bucks, product integration – which NBC’s The Office, for one, relentlessly featured.

Representative sample from chief Dunderhead Michael Scott.

I want my old job back. I want my old parking space back. I want a [Chrysler] Sebring.

This is going to be the best Christmas ever. My girlfriend Carol is coming to our party tonight, and I have a little surprise for her. [singing] I’ve got two tickets to paradise! Pack your bags, we’re leaving the day-after-tomorrow! Um, taking her to Sandals, Jamaica, all-inclusive. All-inclusive. You know what that means? Right? Yeah.

What’s my favorite thing about Hooters? I’ll give you two . . . boobs and hot wings!

Chili’s is the new golf course. It’s where business happens.

Other product placers on The Office included Staples (natch), the video game Call of Duty, and the online virtual world Second Life.

Around the same time, FX’s It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia was even more shameless at shilling (as you might expect, lots of beer brands and bar snacks).

Product placement also found fertile ground in reality TV programs. Bravo’s Project Runway, for instance, custom-tailored four appearances for Chrysler and five for Hilton Hotels into a single 2010 episode.

Ditto for broadcast network soap operas like Days of Our Lives, where there was always room for Cheerios, Chex Mix, and Midol.

The wave of products paying to pop up on-screen crested in a 2011 documentary produced by Morgan Spurlock, who had previously deep-fried McDonald’s in the 2004 film Super-Size Me.

Here’s what Brooks Barnes wrote in the New York Times about Spurlock’s 2011 film: “‘The Greatest Movie Ever Sold’ . . . is Mr. Spurlock’s humorous attempt to dissect the world of product placement, advertising and marketing by making a film financed entirely by product placement, advertising and marketing.”

Incredibly, Spurlock convinced 15 companies – from JetBlue to Ban deodorant to Pom Wonderful juice – that they should actually pay to put their reputations at risk.

It was all upside for Spurlock, though, as he told Entertainment Weekly,

EW: Obviously by bringing all these corporations into your project, you were risking essentially selling out your own movie.

Spurlock: Yeah, but I’m not selling out — I’m buying in! [laughs]

Paging Mr. Escher. Paging Mr. M.C. Escher.

• • • • • • •

The 21st Century march of stealth marketing, not surprisingly, went well beyond product placement.

Also popular were print publications that brands began producing to replace mainstream media as advertising vehicles.

From Rachel Strugatz at WWD:

Social Media Breeds Edvertorial

Bold color may have been the new black on spring runways, but when it comes to the influx of designers creating branded content on the Web, editorial is the new advertising.

“We’re publishing content in an authentic way, and if it’s increasing our brand awareness, then it could be defined as advertising. It’s a new way of communicating with consumers,” Miki Berardelli, chief marketing officer at Tory Burch, said of the changing definition of advertising. “It’s taking an editorial approach to telling your brand story, and the social-media space just lends itself so beautifully to that combination.

New York Times media critic David Carr noted that luxury brands were essentially looking to reach consumers by eliminating traditional media and creating seamless hybrid marketing publications. Here’s how a Hearst magazine executive described it.

The old line separating church and state is not gone, but is definitely a more blurry one. And brands that are authentic, not shameless or opportunistic, have a chance to create content that people will pay attention to.

Of course, ads in sheep’s clothing are by definition inauthentic and opportunistic.

But why get technical about it.

Reality TV Shows Get All Sponsorific

What’s better than product placement, you might ask? Product integration – where your brand is not just sitting on a coffee table, but is actually part of the action.

And in 2012 no media vehicles had more marketing action than the tsunami of reality TV programs that emerged at the time, according to the website Media Dynamics (now apparently defunct).

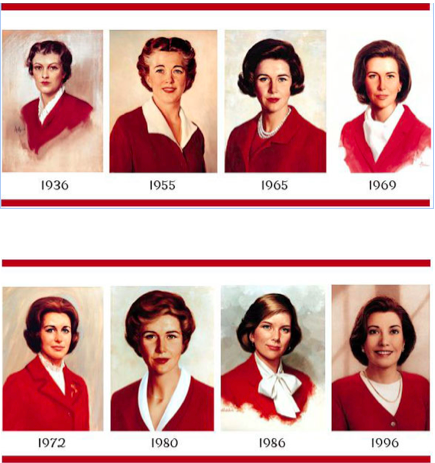

The top 10 primetime shows for product placement activity on broadcast TV networks were all in the reality genre, according to Nielsen. Measuring 11 months in 2011, Nielsen found that Fox’s American Idol led the list with 577 “occurrences,” followed closely by NBC’s The Biggest Loser with 533. Clearly, reality show producers are more amenable to product placements, compared to their counterparts making serious dramas, sitcoms or newsmagazines.

Helpful graphic:

Number three on the hit list, NBC’s Celebrity Apprentice, was to product integration what plaid was to Bermuda shorts.

From Wayne Friedman’s piece in MediaPost:

One of the original big-ticket branded entertainment-connected TV shows, “Celebrity Apprentice” has announced a new slate of in-show sponsors: food company Kraft, drug retailer Walgreens and confectionary brand M&Ms.

NBC has also announced some of last season’s — General Motors, Good Sam, and Farouk Hair Systems — will be making a return for the show. Now in its 12th edition, it premieres on Sunday, Feb. 19. Other season sponsors this year include Entertainment.com, Ivanka Trump Collection, O-Cedar and Five Star Fragrance.

That’s more tie-ins than an East Hampton’s marina.

All in a day’s grift, of course, for Donald J. Trump.

State of the Cuisinart Marketing

It was as if advertising, politics, and news all got stuffed in a blender and somebody hit the purée button. What poured out was native advertising – marketing material tricked out to look like the editorial content surrounding it.

Native ads first emerged in 2009, and by 2012 they were all the rage in stealth marketing, as MediaPost’s Joe Mandese reported.

The Natives Are Restless: News Publishers Move Line Distinguishing Edit, Ad Content

If there is a red line delineating the church and state of journalism, some big news publishers have just crossed it — introducing a spate of new “native” advertising formats that blur the line between advertising and editorial content in new ways, including brand-produced videos served directly in the news organizations’ video news players. The publishers, which include NBC News and Forbes, are not sheepish, much less apologetic about moving the line more to the advertisers’ side of the ledger, but say it is part of an inexorable — indeed an inevitable — shift merging the “storytelling” of their organic journalism with those of their advertisers.

As Meredith Levien, group publisher and chief revenue officer of Forbes Media, told Mandese, “It’s basically just like editorial content.” The idea, she added, was to make the Forbes BrandVoices video ads “so native” that they would replace actual news coverage as the most popular content.

Talk about saying the quiet part out loud: Forget about journalism’s mission to interest the public in the public interest. Levien was all in on journalism milking the public for interest and dividends.

(Levien joined the New York Times the following year, eventually rising from head of advertising to chief revenue officer to COO to CEO, which explains a lot about the myriad times the Grey Lady would open the kimono following Levien’s arrival at the paper.)

Levien’s NativeSpeak at Forbes was consistent with the cooked-up rationale that stealth marketers routinely used to justify their sleight-of-ads: That consumers want a seamless stream of content uninterrupted by advertising.

Again from Mandese:

[One marketing executive] says he believes the new native ad formats actually are more appropriate and authentic for contemporary news audiences because there has been a generational shift in the way they consume content and the way people communicate in general.

“Especially with the new generation, if it’s in advertising, it’s suspicious,” he says.

In other words, we’re tricking you for your own good.

Some other digital publishers went even further. Around the same time Forbes was flogging BrandVoices, Keith Hagey of the Wall Street Journal reported that “the sharing of sponsored content is the centerpiece of BuzzFeed’s business model. [CEO Jonah] Peretti is so sure about the premise that he has dispensed with traditional banner advertising entirely.”

One notable marketer that jumped on the BuzzFeed brandwagon was Barack Obama’s reelection campaign, as Nieman Journalism Lab’s Justin Ellis noted.

The Obama for America content consist of campaign videos on pages that look similar, if slightly less busy, to most posts on BuzzFeed. One exception is the pages come with more overt labeling, spelling out that it’s “Paid Political Content” for readers. But it’s more or less political ad content adapting to the form, taking the same approach BuzzFeed uses with companies like JetBlue or Virgin Mobile.

Granted, our eyes aren’t what they used to be, but that “Paid Political Content” labeling above the headline is not exactly what we’d call overt. But why get technical about it.

(To be sure graf goes here)

To be sure, transparency was one big tug of war between publishers and native advertisers from the outset, since the effectiveness of native ads is largely dependent on deception: The less it looks like advertising, the less it comes across as commercial propaganda.

Back when native ads first emerged, the conventional wisdom was that consumers had a built-in skepticism about advertising, while assigning greater credibility to editorial content. In a post-Trump era, that distinction is no longer so cut-and-dried.

Regardless, the push and pull between publishers, who want to maintain their editorial integrity, and marketers, who want to maximize their investment, continues to this day.

Journalists Get Forced Onto the Dark Side

Of course, somebody had to create all those new native ads, and at certain publications that task fell to the journalists who worked there.

Alternet’s Jonathan Sas captured reporter Jameson Bercow’s experience in this 2013 piece.

“I hate it. I hate doing it… It’s not what I signed up for.” That’s the lament of a former Postmedia reporter assigned all too often to write “custom content.”

Most of us assume that media outlets still go about producing their news the traditional way — a reporter sniffs out a lead or an editor assigns an evolving story or, these days, a columnist storifies a flurry of Twitter activity.

Increasingly, however, stories are put into motion differently. Referred to variously as custom content, custom publishing or directed content, Canada’s major broadsheets and newsmagazines are now speckled with content spun up by marketers and brand sponsors.

Here’s an example Alternet’s Sas provided of the custom content that Berkow was assigned to write for Canada’s The National Post.

Lodging in luxury in an oilsands’ labour camp

CONKLIN, ALBERTA — No career opportunities were available to Melissa Udala in the Okanagan Valley region of British

Columbia where she was raised.

So when her fiancé got a job cooking for hungry Statoil Canada Ltd. workers up at the Norwegian company’s Leismer Lodge near the tiny northern Alberta hamlet of Conklin, she decided to tag along, finding a job answering phones at the front desk. A little more than one year later, the 22-year-old is the front desk manager and has no regrets.

“This is a great place,” she said in between responding to requests from the 480 staff the camp houses. “They took care of me and helped me grow with my career. You can’t find that too much anywhere else, where people want to help you.”

The bottom line, according to Alternet’s Sas: “Though the stories were not, to his knowledge, ever looked at or approved by the sponsoring advertisers, Berkow was uncomfortable with having his byline on content he did not believe could be properly considered journalism.”

Worse than that, readers weren’t told explicitly that a marketer – in that case Statoil Canada – had paid for the piece.

Similar editorial shenanigans were underway at Gawker Media, where founder Nick Denton said he had seen the future, and it was “commerce journalism.”

As Yannick LeJacq reported in International Business Times, Denton said in a leaked memo that he expected “at least 10% of the company’s revenue in 2013 to come from e-commerce activity.” The plan was to hire “commerce specialists” at the company’s various publications. Gawker’s job description for those specialists included lots of helpful background info.

What You’ll Do

Your beat is helping readers buy things. You’ll be delivering content about products that . . . readers know, love, or should own. You’ll have both a daily writing assignment and the freedom to pursue your own content ideas. If you’re interested in things like deal forums, coupon codes, giving your friends product advice, and Amazon.com, you’ll use all of those as inspiration to create your own new commerce content product.

Overall, the job listing added, commerce journalism is “a brand new thing that merges writing and product curation. Most importantly, it adds value to our readers [sic] lives.”

To call that eyewash is an insult to saline solution everywhere. What that grift ultimately “added value to” was less readers’ lives than Gawker’s bottom line.

(To be fair graf goes here)

To be fair, some journalists migrated to the stealth marketing dodge on purpose, as New York Observer reporter Kara Bloomgarden-Smoke chronicled.

Until December, Melissa Lafsky Wall was the editor of Newsweek’s iPad edition, a job she landed on the strength of bylines in The New York Times, Salon, Wired and The Christian Science Monitor, as well as editing stints at the Huffington Post and the Freakonomics blog.

But as Newsweek was laying off staffers leading up to the death of its print edition, Ms. Lafsky Wall decided to go in an altogether new direction: since January, she has been the director of content at HowAboutWe, a startup dating site with a blog about courting, relationships and romance.

And what kind of content, you might ask, did Ms. Lafsky Wall direct at HowAboutWe? Representative samples include “Millennial Women Rejoice: It’s Our Hookup Culture, Too,” “The Adventures of Dating in Davos,” and “Beware the Rom Com Curse, Says Science.”

That seems like pretty run-of-the-mill marketing, but it’s definitely not journalism. As Ms. Bloomgarden-Smoke noted, “Ms. Lafsky Wall is one of many journalists departing the desert of traditional media for the greener—but also grayer—pastures of branded content.”

A bad year for journalism, owing to layoffs at Condé Nast, Martha Stewart Living, Reuters and Hearst, and buyouts at The New York Times and Time Inc., has been a boon to this emerging field. While writing gigs at magazines and newspapers continue to dry up, there are abundant opportunities to write or consult for blogs owned directly by brands.

Ms. Lafsky Wall was perfectly happy with the tradeoff. “Working in a place that’s growing is amazing. Growth and progress … it’s like, thank God!” she told Ms. Bloomgarden-Smoke. “And having a budget to pay writers is amazing.”

Nice way to make a living, right?

Not so fast, said British transplant Andrew Sullivan, who at the time produced a popular blog called The Daily Dish and who published a blistering post about native ads, with BuzzFeed as his whipping boy.

After noting that “[once] you slip into the advertorial vortex at Buzzfeed, everything that is advertizing appears as non-advertizing,” Sullivan drops the hammer.

Maybe I’m old-fashioned but one core ethical rule I thought we had to follow in journalism was the church-state divide between editorial and advertizing. But as journalism has gotten much more desperate for any kind of revenue and since banner ads have faded, this divide has narrowed and narrowed. The “sponsored content” model is designed to obscure the old line as much as possible (while staying thisclose to the right side of the ethical boundary). It’s more like product placement in a movie – except movies are not journalism.

Sullivan’s conclusion: “I have nothing but admiration for innovation in advertizing and creative revenue-generation online. Without it, journalism will die. But if advertorials become effectively indistinguishable from editorial, aren’t we in danger of destroying the village in order to save it?”

The Sneak in Review (2013 Year-End Edition)

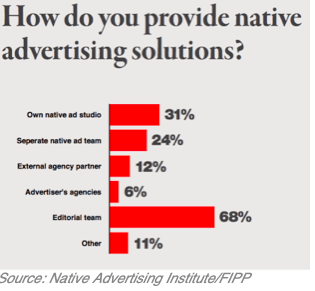

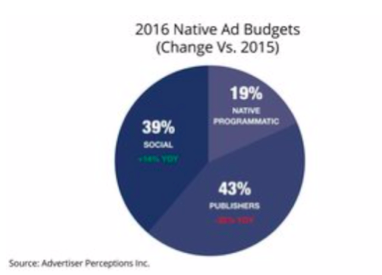

Around the close of 2013, stealth marketing was seen as media manna from heaven by advertising agencies, consumer brands, and digital publishers alike.

For ad agencies, it was something innovative they could pitch to clients – at a premium price point.

For brands, it was a new – and potentially more effective – way to reach consumers.

And for publishers, it was a welcome source of revenue that wouldn’t be pirated by the Google/Facebook digital ad duopoly. It also might offset in part the knee-buckling revenue declines publishers had experienced during the past half decade.

Understandably, then, all three were on stealth marketing like Brown on Williamson.

According to one survey, 62% of publishers offered branded content/native advertising and another 16% planned to do so in the following year.

Beyond that, Jack Loechner at MediaPost noted, “41% of brands and 34% of agencies currently use native advertising, with an additional 20% of brands and 12% of agencies planning to begin using it within the year.”

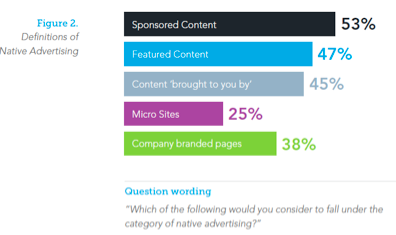

Part of the whole sleight-of-ad game resided in the multiple labels that marketers attached to native advertising, as illustrated in this graph:

Presumably, the more different labels you assign to native advertising, the less prevalent it might seem to be to the media hall monitors. Staying under the radar is, after all, the name of the game.

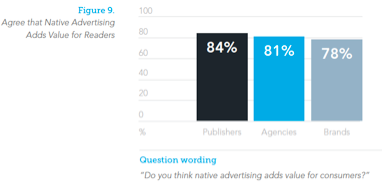

Even more worrisome was the “Agree That Native Advertising Adds Value for Readers” chart.

To recap: 84% of publishers, 81% of agencies, and 78% of brands believed that tricking consumers was in the interest of consumers.

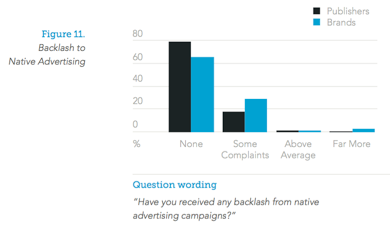

Most worrisome, though, was the “Backlash to Native Advertising” chart.

If that survey is to be believed, roughly two-thirds of consumers were fine with being deceived by advertisers.

That, my friends, was bound to become a problem sooner rather than later. And, in fact, it did.

Wall Street Journal Makes ‘Faustian Pact’ with Native Advertising

It was only a matter of time before national daily newspapers jumped into the stealth marketing pool. That time turned out to be early in 2014, and the jumpiest newspaper turned out to be the Wall Street Journal.

As Advertising Age’s Michael Sebastian reported:

The Wall Street Journal is introducing native advertising to its website less than six months after Editor-in-Chief Gerard Baker described many publishers’ moves in the arena as a “Faustian pact.”

For those unfamiliar with German folklore, that’s a deal with the devil.

Journal executives willingly made that deal, forcing Baker to walk back his comments, as Chris O’Shea reported at MediaBistro’s website FishbowlNY:

“Our readers trust us, and the WSJ Custom Studios team has created clear and thorough labeling guidelines around the advertiser’s content in order to protect that trust,” Baker said. “I am confident that our readers will appreciate what is sponsor-generated content and what is content from our global news staff.”

Readers will appreciate the difference between sponsor-generated content and news content?

Maybe.

But more likely they’ll ignore the native ads. At least that’s what Peter Kafka said in this Re/code piece.

Advertisers love the idea of “native ads” — marketing messages that sort of look like “real” content — because they think that Web surfers who ignore other ads will pay attention to the new format.

This sounds interesting in theory, but less convincing when you actually look at the stuff native advertisers are creating, which often resembles lousy versions of “real” content — stiffly written advertorials that no one except the person who paid for it would ever willingly look at.

And, sure enough, very few people are looking at this stuff. Or, more precisely: People who look at this stuff can’t wait to stop reading it.

Here’s the thing: According to Web traffic analyst Chartbeat, 71% of readers will stick with a news article for more than 15 seconds, but only 24% will last that long for native ad content.

Regardless of results, publishers fell deeper and deeper in love with the revenue generated by native advertising. The Washington Post, for one, decided to try shrinking the gap between news stories and native ads, as Adweek’s Lucia Moses reported.

The Washington Post’s Native Ads Get Editorial Treatment

Even as native ads naysayers argue for clear labeling and design cues so readers don’t confuse them with actual journalism, publishers and advertisers have pushed to make the units look more like editorial.

The latest example comes from The Washington Post. Its native ad program, WP BrandConnect, is adopting the multimedia, longform template that’s been used in the newsroom for features like this one.

More bad news from Adweek’s Moses:

Apparently, the [Washington Post’s] BrandConnect tweaks are just the beginning of what could be a cozier relationship between news and advertising. The Post is offering advertisers the ability to take advantage of its Truth Teller video project, which originally was used to fact-check politicians’ speeches and has since been expanded to trailers of movies based on true stories, like The Wolf of Wall Street and 12 Years a Slave.

It’s also embedding technologists with the sales side to speed up the development of complicated ad units.

Fact checkers plus movie trailers plus tech geeks plus sales guys? The corn, at that point, was totally off the cob.

Fallon Gone: The Tonight Show Brings GE to Life

Since its debut 67 years ago, NBC’s The Tonight Show has featured more plugs than Joe Biden’s head. But the 2014 introduction of GE’s Fallonvention segments, replete with the GE logo on everything from lab coats to oversized $5000 checks for young inventors, represented a new low for the late-night fixture.

Here’s an NBC promotional still for the series.

Saya Weissman had the details in this piece for Digiday.

GE takes a deep dive into native advertising

Last month, Jimmy Fallon had a group of teen inventors come on “The Tonight Show” to show off their gadgets. Anne, 16, showed

off her flashlight powered by the heat of the human hand. Jonathan, 13, created something called an “iHead,” which is essentially headgear with your iPhone attached to it via suction cup.

This young-inventors showcase is called “Fallonvention,” or rather “GE’s Fallonvention,” and it will be a reoccurring segment on the late night talk show featuring young inventors and their creations, along with Fallon’s own funny inventions and commentary. This is what branded TV looks like. And it is part of GE’s latest big push into the industry’s buzzed-about ad format: native advertising

According to Linda Boff, GE’s executive director of global brand marketing, “great content can come from a lot of different places, but funnily enough, it seems to be traditional media can get a little more attention when it comes to native.”

Funnily enough?

Not everyone was laughing.

Did Native Ads Croak NYT’s Executive Editor?

In the spring of 2014, the favorite parlor game among the media chinstrokerati was What Got Jill Abramson Axed by the New York Times?

Rucjhika Tulshyan at Forbes, for instance, asked if Abramson got the boot because she was too “bossy.”

The New Yorker’s Ken Auletta focused on the stink Abramson raised when she “discovered that her pay and her pension benefits as both executive editor and, before that, as managing editor were considerably less than the pay and pension benefits of Bill Keller, the male editor whom she replaced in both jobs.”

Politico’s Dylan Byers reported that “New York Times publisher Arthur Sulzberger fired executive editor Jill Abramson after concluding that she had misled both him and chief executive Mark Thompson during her effort to hire a new co-managing editor, according to two sources with knowledge of the reason for her termination.”

Perhaps the most intriguing post-mortem, though, came from a piece by MediaPost’s Erik Sass.

Some observers wondered whether Abramson was forced out for disagreeing with the NYT’s implementation of native advertising, a key part of its business strategy as it seeks to replace declining print ad revenues.

In May 2013, Abramson told the Wired Business Conference: “What I worry about is… leaving confusion in readers’ minds about where the content comes from, and purposefully making advertising look like a news story. I think that some of what is being done with native advertising does confuse a little too much.” However, in his remarks to the newsroom Sulzberger was quoted as saying the rupture was “not about any sort of disagreement between the newsroom and the business side.”

Of course Sulzberger would say that. But it’s likely not a coincidence that one year earlier Meredith Levien (she of “native advertising is basically just like editorial content”) had migrated from Forbes to the Times as head of advertising.

According to a MediaPost piece by Karl Greenberg, Levien touted native ads at a digital marketing conference about a week after Abramson had been defenestrated.

Native advertising, [Levien] said, exploits the form, factor, discovery mechanism and production values of the surrounding content, taking the shape of the storytelling around it and aspiring to similar engagement.

That aesthetic will be at the center of the rediscovery of great ads for the digital age — something that she said hasn’t exactly happened.

In the ensuing years, as we will see, Levien would do her level best to make sure it did exactly happen.

Time Inc. CEO: Editors Are Happier Reporting to the Business Side

That was the headline on a blog post in mid-2014 by the estimable media critic Jim Romenesko (sadly – and oddly – his media blog has been replaced by some kitchen website),

Here’s the lede from that 2014 piece:

Last fall, new Time Inc. CEO Joe Ripp told his editors that they’d be reporting to the business side rather than to the editor-in-chief – a move that Ad Age said “sent a ripple of anxiety” through the company’s editorial offices.

Bloomberg TV asked Ripp this morning how editors are dealing with that change. “Frankly, I think they are happier,” he said.

Ripp also said this:

They are more excited about it because no longer are we asking ourselves the question are we violating church and state, whatever that was. We are now asking ourselves the question are we violating the trust with our consumers? We’re never going to do that. But within the framework of that, my editors have much more freedom to think about how I can delight my consumers, how I can work with advertisers, how I can think through the problems.

Editors looking to delight their consumers? Editors looking to work with advertisers? Yeah, they’re livin’ the dream alright.

Time Inc., as it happened, wasn’t the only media company blurring the line between advertising and editorial. Also needing a V.P. of Optometry around the same time was the outfit running Inside Tucson Business magazine, which issued this manifesto to its editors: “Many companies in our industry have wrongly divided their focus among many customer groups. We do not. Our customer is the advertiser. Readers are our customers’ customer.”

That clearly made Inside Tucson Business a wholly owned subsidiary of its advertisers. Time Inc.’s time to play that same role was still to come.

Time Inc. to Its Writers: Be Ad Friendly – Or Else!

The Fall of the House of Luce began in 2014, as Time Inc. started leasing out its editorial side to advertisers. Time Inc.’s chief content officer (read: chief stealth marketer) Norman Pearlstine described his approach to the advertising/editorial relationship in this WWD interview.

I think that the balancing act is that you would like to find appropriate ways to have editorial talent working with [head of corporate advertising Mark Ford] and his team to come up with content solutions for advertisers and, at the same time, you have to be obviously mindful of potential conflicts if you are not careful in how you structure these things. The Time Inc. Content Solutions model is one to follow in that it’s got some very experienced journalists working on those products but they don’t engage in magazines on editorial where they’d be covering the people that they are writing about.

Translation: Time Inc. journalists would have to produce marketing material about whatever they didn’t cover.

Less than a week after Pearlstein’s WWD interview, Gawker’s Hamilton Nolan detailed how the new system worked.

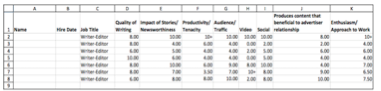

Here you see an internal Time Inc. spreadsheet that was used to rank and evaluate “writer-editors” at SI.com. (Time Inc. provided this document to the Newspaper Guild, which represents some of their employees, and the union provided it to us.)

The evaluations were done as part of the process of deciding who would be laid off. Most interesting is this ranking criteria: “Produces content that [is] beneficial to advertiser relationship.” These editorial employees were all ranked in this way, with their scores ranging from 2 to 10.

Newspaper Guild union rep Anthony Napoli had this to say: “Time Inc. actually laid off Sports Illustrated writers based on the criteria listed on that chart. Writers who may have high assessments for their writing ability, which is their job, were in fact terminated based on the fact the company believed their stories did not ‘produce content that is beneficial to advertiser relationships.'”

A spokesman for Sports Illustrated got back to Gawker with some world-class gobbledygook about the evaluations being conducted “in response to the Guild’s requirement for our rationale for out of seniority layoffs.”

Regardless, the meaning of the evaluations was clear to the magazine’s writers and editors: Time was not on their side.

The Grey Lady Shows Some Leg

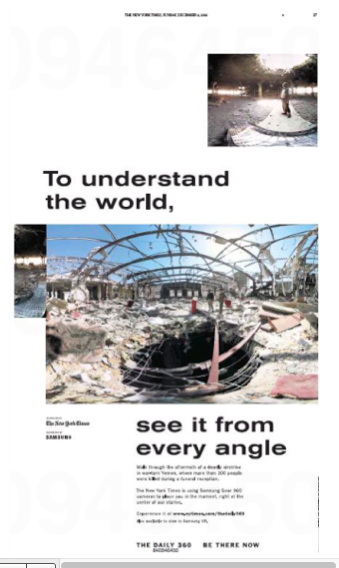

The New York Times Co. jumped into the stealth marketing pool in 2014 when it introduced T Brand Studios, an in-house shop dedicated to producing “custom content.”

As Nieman Lab’s Joseph Lichterman noted at the time, “since launching earlier this year, [T Brand Studio has] struck deals with 32 different brands – from Netflix to Thomson Reuters – to create ads that cost from $25,000 to more than $200,000 just to create.”

Representative sample: T Brand’s native ad for the second season of Netflix’s Orange Is the New Black, a multimedia presentation that examined the challenges women face in prison.

Upper left at the top of the ad was this:

![]()

and upper center was this:

![]()

The ad itself:

Over the past three decades, the number of women serving time in American prisons has increased more than eightfold.

Today, some 15,000 are held in federal custody and an additional 100,000 are behind bars in local jails. That sustained growth has researchers, former inmates and prison reform advocates calling for women’s facilities that do more than replicate a system designed for men.

“These are invisible women,” says Dr. Stephanie Covington, a psychologist and co-director of the Center For Gender and Justice, an advocacy group based in La Jolla, Calif. “Every piece of the experience of being in the criminal justice system differs between men and women.”

T Brand Studios claimed that it was “inspired by the journalism and innovation of The New York Times [to craft] stories that help brands make an impact in the world.”

And its Orange Is the New Black ad certainly did that. It featured video interviews with female inmates; charts and statistics; a slideshow of inmate portraits; and text that was rich with research. It got lots of attention and lots of plaudits – even from some journalists.

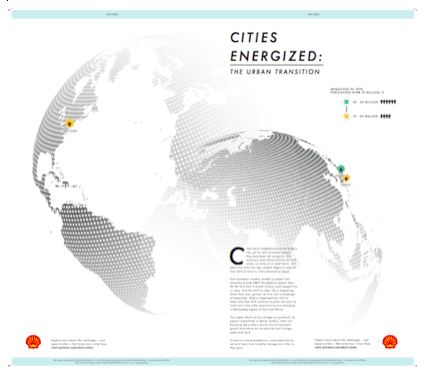

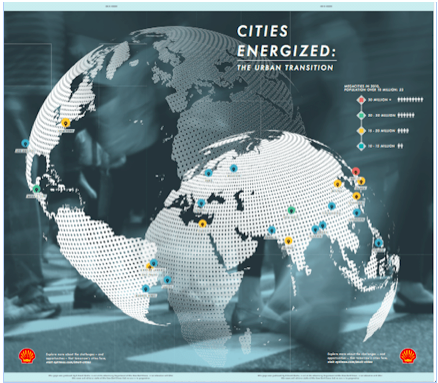

Not long after that, the Times also went native in its print edition, as Lucia Moses reported at Digiday.

The NY Times runs its first print native ad

The New York Times has been producing increasingly elaborate native ads online, and now it has gone a step further by extending the format to print for the first time.

The ad, for Shell, is set to appear in print and online Wednesday, and it’s a far cry from the advertorials of days past. First, the size: The print component is an eight-page section that’s wrapped around home-delivered copies. (In the case of newsstand copies, the ad wraps the business section.) The top sheet is opaque vellum, for extra effect. The print creative extends the Web version, with infographics that show the urbanization of the world’s population.

The section, titled Cities Energized: The Urban Transition, examined the global growth of megacities and the challenges they presented in terms of sustainability and energy efficiency.

Here’s the vellum overlay and an inside page; the red Shell logo appears at the bottom of every page.

Both in print and online, the Times originally got native advertising mostly right: (pretty) clear labeling, legitimate material, responsible presentation. That was a far cry from some other publications, ranging from BuzzFeed’s blurry lines to The Atlantic’s selling its soul to the Church of Scientology and running blatant propaganda.

Then again, the Grey Lady would generate a few wrinkles of her own as time went on. More on that to come.

Magazine Publisher Gets Condé Nasty

In the annals of stealth marketing, 2015 would go down as the Year of the Shanghaied Magazine Editor.

From Condé Nast to Time Inc. to the Hearst magazine chain, editors and reporters were conscripted into producing marketing material in the shape of editorial content.

It all kicked off in January with Condé Nast executives ordering its magazine editors to go native, as the Wall Street Journal’s Steven Perlberg reported.

Write Ads? Condé Nast Staff Is Wary

Allowing Editors to Work With Marketers Would Break Down a Boundary

Condé Nast caused a stir in the media world Monday when it announced plans for a new studio that will allow marketers to work directly with editors at its magazines to create “branded content,” ads designed to blend in with regular articles.

The burning question for media industry observers: Will every one of the company’s magazines have to participate, including those more focused on news, like the New Yorker, Vanity Fair, Wired and GQ?

News organizations generally believe in a wall between editorial operations and the business side of a publication.

The new program, “23 Stories by Condé Nast,” would seemingly break down that boundary, potentially distorting just what is fact and what is marketing.

The branded content studio was named after the 23 floors Condé Nast had recently taken over at One World Trade Center. Eventually recognizing just how bad that name was, Condé Nast re-branded the branded content studio as CNX, “a new full-service creative agency which leverages the unparalleled influence and editorial expertise of Condé Nast through advertising, brand strategy, casting and experiential capabilities.”

But first there was that question the Journal piece posed about the participation of the news-focused magazines.

Some staffers within Condé Nast believe there is wiggle room under the “23 Stories” initiative. Their understanding is that there is flexibility for certain titles to decide they don’t want to have editors involved in producing content for advertisers.

The New Yorker, for example, isn’t inclined to make available its editors, the staffers say.

The company, however, says no magazine title is exempt from the new program . . .

Pity the poor New Yorker magazine staffers, who – in addition to the possible hijacking of their newsroom – had been forced to move into the rat-infested Condé Nast headquarters at One World Trade Center. The magazine itself, though, had already moved into the grift-infested world of stealth marketing.

There was, for instance, The New Yorker’s notorious 2005 sellout of an entire edition to the Target retail chain, with cover art that echoed the Target logo tossed in as a bonus.

Target was the only advertiser in the issue, the first time The New Yorker had done that in eight decades of publishing. And it totally missed the mark within the magazine industry, as Steve Hall noted in Adrants.

Magazine Editors Unhappy With ‘The New Yorker’

It seems the American Society of Magazine Editors – which, oddly, sounds like a bunch of old men sitting around in a smoke-filled country club lounge – didn’t take too kindly to the recent stunt The New Yorker pulled with Target – selling all ad pages, exclusively, to the discount giant. The Society requires magazines with one sponsor to include an editorial statement stating the advertiser had no influence over editorial content. The New Yorker did not include such a note. Whether or not lines were crossed here, Target, as always, accomplished a masterstroke of publicity with this move and is likely sitting back laughing at all of those who have raised issue with the stunt.

Eight years later, The New Yorker was all-in on native advertising, as Josh Sternberg reported at Digiday.

The New Yorker Goes Native

In January, when the Atlantic ran sponsored content on behalf of Scientology, the media world went apoplectic. Last month, when the New Yorker began experimenting with sponsored content, no one made a peep. Times have changed.

Like many publishers before it — from the digital kids at Gawker and BuzzFeed to the more traditional types at the Atlantic to Forbes — the New Yorker has begun running content on behalf of brands. But unlike those who set the stage a year or so ago, there has been little fanfare around that fact that one of the most prestigious publications in print has gone native.

According to a New Yorker spokesperson, the magazine’s native advertising initiative is not very different from other large, integrated programs the Condé Nast imprint has run for numerous advertisers over the years.

(To be fair graf goes here)

To be fair, none of those New Yorker ventures into stealth marketing ensnared the magazine’s editorial staffers. But – to be sure – past performance was no guarantee, as the money guys say, of future results.

Back to Steven Perlberg’s WSJ piece.

The inclusion of Condé Nast’s editorial staff is “the thing that really sets their branded-content offering apart,” said Amy Stettler, general manager of global media and agency management at Microsoft Corp., a Condé Nast advertiser that is still weighing whether to sign on to “23 Stories.”

“Our primary editorial mission remains the creation of original, independent and compelling premium content in all of its forms,” Condé Nast said.

That would be Exhibit Umpteen of SneakSpeak at its very best.

• • • • • • •

Hard on the heels of Condé Nast’s editorial hostage-taking, Time Inc. started executing its aforementioned plan to hijack the chain’s newsrooms, as Adele Chapin reported in the now – sadly – defunct Racked.

Time Inc. Editors Must Write Advertorial Content, Too

No more firewall at Time Inc. between business and editorial.

Time Inc. is the latest publishing company to announce that it is now requiring magazine editors to write branded content for advertisers. AdAge reports that editors at 11 Time Inc. magazines include InStyle and Time wrote content for ads for a Google campaign last fall. The print ads ran between September and December, and featured Google-able questions written by editors to go along with magazine articles.

AdAge provides examples of the ad content written by editors: “In a Time magazine article about flags, for instance, the Google ad asked, ‘OK, Google, how many American flags are there on the moon?’ An InStyle story on “The Scandal” collection at clothing store The Limited included the question, ‘OK, Google, who is the person Olivia Pope is based on?'”

Our question to Time, Inc: Granted this isn’t as bad as when Time founder Henry Luce pimped out his magazine empire to Italian fascism in the run-up to World War II.

But it is bad, right?

National Magazine Awards (Almost) Get Condé Nasty Over Native Ads

Condé Nast’s feet-first foray into native advertising initially went over like the metric system.

One group that considered the company’s advertising-eats-editorial move totally misguided was the American Society of Magazine Editors, as Erika Adams detailed in the late, lamented Racked.

Condé Nast May Not Be Eligible to Receive National Magazine Awards Anymore

WWD’s Alexandra Steigrad reports that the American Society of Magazine Editors is rethinking its guidelines on native advertising now that Condé Nast and other major publishing houses have publicly confirmed that editors will be writing ad content for their brands. As it stands, ASME’s rule on native advertising states: “Editorial contributors should not participate in the creation of advertising if their work would appear to be an endorsement by the magazine of the advertised product.” In light of recent developments, ASME CEO Sid Holt explained to WWD that the old rule is outdated and it’s being updated to reflect that “the primary role of the editor is to serve the reader.”

WWD’s Steigrad also noted that the group would probably not hold firm: “[One] source said, the new principles will be ‘up for interpretation.’’”

Spoiler alert: ASME folded like origami.

The 2016 Ellie Awards “interpreted” that two Condé Nast publications were perfectly acceptable to be honored.

Design

Honors overall excellence in print magazine designWinner: Wired

Feature Writing

Honors original, stylish storytellingWinner: The New Yorker for “The Really Big One,” by Kathryn Schulz, July 20

As they say in The Big Town, I got your editorial integrity right here.

The Smokescreen Naming of Native Ads

On the theory that a moving target is hard to hit, the rise of native ads was accompanied by an increase in the variety of labels attached to them.

During the summer of 2015, Ad Age’s Michael Sebastian provided a helpful glossary.

Media Companies Take Pains To Avoid Scarlet ‘A’ For ‘Ad’

Native Ads Go by Many Names

Media executives insist their native ads are always clearly labeled to avoid confusing readers over which articles came purely from editorial staff and which content an advertiser paid to produce and run.

But an analysis of two dozen news and lifestyle sites, social media platforms and popular mobile apps shows that none of the companies that rely on this strategy for ad revenue actually refers to them in a way most recognizable to consumers: advertisement.

One example was this native ad for Revlon that ran in Refinery29.

For the small-type impaired, here’s how the ad is labeled at the top: “Refinery29 + REVLON Present” – a designation almost as opaque as some of Revlon’s facial products.

Other examples from the Ad Age piece include “Sponsor Content” in The Atlantic, “Brand Publisher” in BuzzFeed, “Sponsored” on Instagram, and both “Paid For” and “Posted By” in the New York Times.

None of them can be reasonably described as “prominent.”

Ad Age also published a helpful chart with the labeling practices of 23 publications, none of which use the word “ad” or “advertising.” The operating philosophy seemed to be something like this: If we call it a whole lot of different names, there might not appear to be so much of it.

File under: A native ad by any other name would sell as sweet.

Except they sort of didn’t . . . as Poynter’s Benjamin Mullin reported in the summer of 2015.

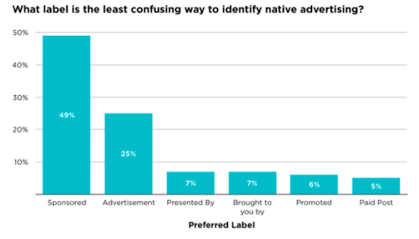

Report: One-third of readers disappointed or deceived by sponsored content

About a third of news consumers in both the United States and the United Kingdom feel tricked or let down by sponsored content or native advertising, according to a new report released this evening by the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

The 2015 Digital News Report also reveals that half of news consumers surveyed grudgingly accept sponsored content on the basis that it helps provide them with free news. But more than a quarter think less highly of the news outlet that publishes native advertising or sponsored content.

Actually, the number in the U.S. who felt tricked was even higher – a whopping 43% were disappointed or felt deceived by stealth marketers.

So how did leading publishers respond? They doubled down.

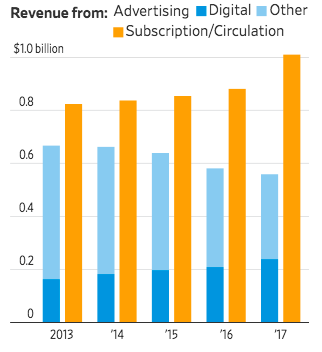

The Economist Group looked to its native advertising division to make up for its reported 46% decrease in print revenue over the previous three years. And the New York Times aimed to double its branded content revenue from 2014 to 2015, according to Ken Doctor’s Media Notebook at Politico.

The Times has found the big budget sweet spot for its T Brand Studio: between $250,000 and $500,000. It now has completed 70 campaigns for 60 advertisers . . .

The Times did $186 million in overall digital advertising in 2014. Of that . . . we can figure the first year of T Brand Studio contributed about $12-15 million.

T Brand Studio actually took in $14 million in 2014 and – wait for it – $35 million in 2015.

And stealth marketing only grew bigger from there.

FTC Tries to Crack Down on Stealth Marketers (Take One)

Despite the aforementioned 43% of readers who felt disappointed or deceived by sponsored content, the Federal Trade Commission was largely AWOL on the issue until the end of 2015, when it started plucking some low-hanging fruit.

First, the FTC busted a couple of app developers for using “persistent identifiers” to collect kids’ information for targeted advertising. The agency also fielded two complaints about the YouTube Kids app, which ran junk-food videos like this one but claimed they were not ads.

Judge for yourself from this screenshot.