In Marshall McLuhan’s landmark work The Medium Is the Massage (it was a printer’s typo he liked so much he stuck with it), the legendary media guru noted that “Real news is bad news – bad news about somebody, or bad news for somebody.”

Enter the latest reports about native advertising, which are bad news for just about everybody – journalists, publishers, and consumers.

Start with . . .

Bad News for Journalists

The hardtracking staff has chronicled multiple instances of publications shanghaiing editorial staffs into creating what’s often called “brand journalism.” But Greg Dool’s piece in Folio reveals just how rampant the practice has become.

Majority of Publishers Use Their Own Editorial Staffs to Produce Native Ads

Native advertising is only the latest new skill set taken on by editors in the digital age.

So, you’re a reporter. Can you code?

Just exactly what it means to be a magazine journalist in the 21st century is a question that seems to be posed quite often in this industry, and no two answers are generally the same. Regardless of who you ask though, one universal truth permeates: you need to wear a lot of hats . . .

Journalists need to be tech-savvy, capable of thinking across platforms, well-versed in social media and video editing, with the ability to fact check and copy edit on the fly.

Now, add to the list native advertising production.

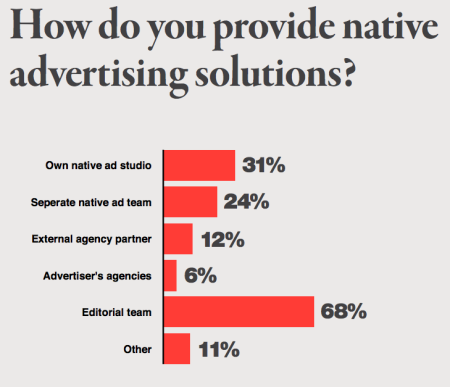

A study from FIPP and the Native Advertising Institute found that over two-thirds of magazine publishers employ their own editorial staffs to produce native ads.

Helpful chart:

Drive us nuts graf:

When asked to name what they considered the biggest threat to native advertising, respondents cited a “lack of seperation [sic] of the editorial and the commercial side” as the number one concern.

Wait, what?

The “lack of seperation” is the whole point of native advertising, which is to create marketing material that masquerades as editorial content. So that leads to this: “11 percent of respondents to the survey say they don’t label native advertising, although another 24 percent report marking native ads with only ‘a different look and feel.'”

In other words, ads in sheep’s clothing.

Problem is, marketers are having trouble counting those sheep. Which is . . .

Bad News for Publishers

From Max Willens at Digiday:

Back to our sponsor? Why publishers struggle to renew native advertising

Sponsor content was supposed to be publishers’ ticket to digital sustainability. Turns out most of them are having a hard time getting advertisers to come back for seconds.

Digital ad sales intelligence platform MediaRadar said the average renewal rate for sponsor content this year is 21 percent. Meanwhile, native ad tech company Polar recently described renewal rates as “weak,” with 40 percent of the publishers it surveyed showing renewal rates below 50 percent.

That’s a big problem, considering that native ads are supposed to be the salvation of online publishers. “BuzzFeed relies on it as its primary source of revenue, and publishers like The Atlantic and The New York Times look at it as a major source, too: The Times is looking to its T Brand Studio to help it generate $800 million in revenue by 2020, while The Atlantic expects to get 75 percent of its ad revenue from native this year.”

(Fun fact to know and tell: Three years ago around 15 companies produced native ads. Now 600 do.)

At the heart of the matter: Marketers have no idea if native advertising actually produces any return on investment. Which brings us to . . .

Worse News for Consumers

As it happens, the less marketers adhere to Federal Trade Commission guidelines for native advertising, the better the stealth ads work. From Joe Mandese’s piece in MediaPost’s MediaDailyNews:

Study Finds Third Of Native Ads Fail To Comply, Perform Better Than Fed Guidelines

About a third of native ad placements fail to comply with federal disclosure guidelines, according to an analysis released this morning by a leading native advertising developer.

More significantly, the study suggests publishers may not be complying because the explicit nature of federal recommendations may not perform as well as more ambiguous approaches favored by some publishers and advertisers.

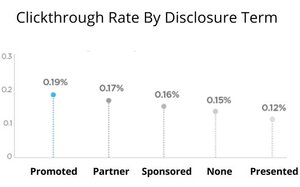

Turns out about half of the publishers surveyed used the term “sponsored,” and only 4.5% used the term “advertisement,” which the FTC prefers as a label for paid content. But most marketers prefer more ambiguous terms like “promoted,” “presented,” or “partner.”

That’s meaningful, according to another helpful chart.

So all that’s the bad news.

You say you want some good news? Try this: According to Pew’s State of the News Media 2016 report on Digital News Revenue, “the sponsorship category, which includes the native advertising format being used by publishers such as BuzzFeed, The Atlantic and others, saw less growth, at 9% to $1.7 billion. It accounts for just 6% of total display spending, making it the smallest category.”

So maybe the “salvation of online publishers” is a false Mediasiah.

Maybe that’s good news.

Maybe not.

You tell us.

John R. Carroll is media analyst for NPR's Here & Now and senior news analyst for WBUR in Boston. He also writes at Campaign Outsider and It's Good to Live in a Two-Daily Town.

John R. Carroll has 305 post(s) on Sneak Adtack